Automatically Creating Your Carbon Footprint with AI

Inspiration source: start with why

This case study retraces the steps that allowed us to design, in just two months, a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) leveraging artificial intelligence. Our objective: to maximize the value of sustainability consulting by drastically reducing the time spent on manual, repetitive, and tedious tasks.

Why? Prioritizing Consulting Over Data Processing

Before reducing its environmental impacts, a company must understand where its greenhouse gas emissions come from. This involves measuring its carbon footprint, including its own activities and those of its suppliers.

This footprint helps identify "hotspots" (the highest-emitting areas) to prioritize actions that significantly reduce environmental impacts. If we draw a parallel with traditional accounting: just as you analyze high-expense items to optimize costs, you analyze major emission sources to reduce the carbon footprint.

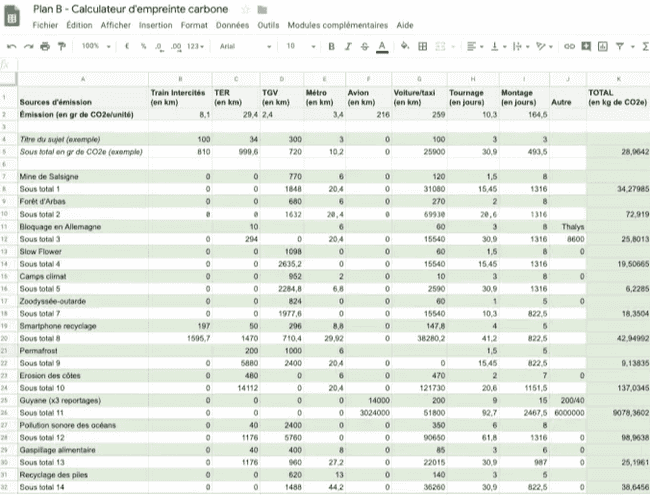

One of the challenges in producing this footprint lies in data collection and classification. A common approach is to start with purchasing data (invoices, ERP systems, Excel files) and cross-reference them with emission factor databases (such as ecoinvent) to associate a carbon impact with each product or service.

It is essentially accounting where the unit price of a purchased product is replaced by its greenhouse gas impact. You multiply the impact by the quantity of product purchased and sum everything up to determine the company's global footprint.

Source: ladn.eu, excerpt from Le Monde's carbon footprint.

Just as companies hire accountants for their financial books, they can call upon sustainability experts for their carbon accounting. The intervention of an expert is often crucial to ensure the right match between collected data and emission factor databases. This is precisely where we come in.

Our partner, an expert in the field, requested our support to accelerate this process, which remains largely manual and time-consuming. This is a context where artificial intelligence can provide invaluable assistance.

How? AI to the Rescue

How do we implement a system capable of automatically linking a product to the most relevant emission factor?

Data access is a major challenge in AI development. Precise supply chain information is confidential, making it difficult to train models on proprietary data—a process that is often expensive, technically arduous, or even legally restricted.

Fortunately, techniques exist that allow us to rely on open-source AI models without requiring massive internal datasets.

By using zero-shot learning, embeddings, and sentence similarity calculations, we implemented a system that matches a product name with an emission factor name.

Zero-Shot Learning: Definition

This is the idea of using a general-purpose model (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Mistral, Apertus, etc.) already trained on a vast corpus of text to solve a specific problem (in this case, matching two texts: a product description and a reference in an emission factor database). Performance is generally sufficient to produce usable results quickly, without a heavy data collection or annotation phase.

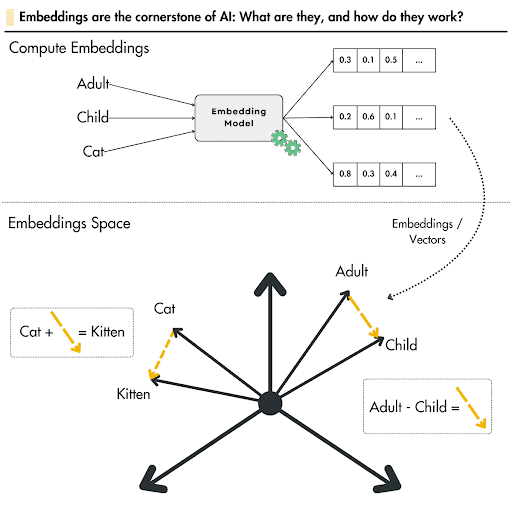

Why Use Embeddings?

This technique, which predates LLMs, allows words, expressions, or sentences to be converted into a numerical sequence—specifically, vectors.

Historically, models like Word2Vec or GloVe were used to translate words into vectors, but they did not use the same architecture as current Large Language Models (LLMs). Today, the best embedding methods rely on LLMs based on the Transformer architecture. These models (like BERT or GPT) generate vector representations that are much richer semantically and contextually, marking a clear improvement over previous approaches.

This technique compares texts not based on word similarity, but on the meaning they convey. For example, although the words "adult" and "child" are different, they share the semantic concept of "age."

The illustration below provides an example. It uses vectors in a three-dimensional (3D) space to show that the distance between two vectors can represent the dimension of age.

It is important to note that in current practice, vectors generally have around 4096 dimensions (making them difficult to visualize). Moreover, the distance between these vectors does not carry a meaning as simple to interpret as in a 3D example.

Source: lightly.ai

In our case, we use this comparison technique to find which entry in a dictionary (the impact database) best corresponds to the products found in accounting spreadsheets.

Example: Company K bought 5 tons of cotton to make T-shirts; the closest name in the ecoinvent database will be "market for fibre, cotton."

“cotton” - “market for fibre, cotton” < “cotton” - “market for electricity, low voltage”

For each product in our inventory, we look for the phrase that is most semantically similar to those in the emission database.

What? A First Iteration for Rapid Feedback

On paper, everything looks promising; now we need to validate the idea with a model and real data.

We quickly validated the approach through a few days of testing with product lists from public data. For the embedding (transforming words into vectors), we selected small open-source AI models. Powerful LLMs (like ChatGPT), designed for generation and reasoning, are overkill for simple vector transformation. Using such models would be expensive and unnecessarily complex (over-engineering).

To identify the best model(s), we relied on Hugging Face leaderboards, which compare models across different semantic similarity benchmarks. All these tests are based on a simple principle: calculating the "distance" between two vectors.

After some experimentation, we concluded that the model achieved a high percentage of "true" matches. Experts are still better, but the results were satisfactory enough to deploy the first version of our PoC. This transformed the tedious task of searching for every match into a validation process, using a score provided by the model to aid decision-making.

To encourage rapid adoption and reduce development time, we deployed a very minimalist user interface. Initially, users could get results quickly by simply providing an Excel file as a data source. The tool then fills in a column with the corresponding reference extracted from our impact database.

Within days, the service was deployed and presented to the teams. User feedback was immediate. The strongest request was to account for product location—a vital criterion for impact calculation.

Before improving the model or the UX, we focused on implementing this request. Two weeks later, the MVP was ready; it was truly "Viable" for the users.

Next?

Following the initial usage feedback of the MVP, future iterations aim to leverage expert knowledge to influence the model's choices, thereby increasing its performance.

Three possible iteration examples:

- User Experience: Helping experts focus and work in more detail on specific hotspots (e.g., energy used for freight transport) through an interactive report showing the largest impact sectors with confidence levels for quick decision support.

- Model Refinement: Improving the model to better characterize flows (e.g., guiding the model to favor renewable energy emission factors for a specific industry sector to be more precise).

- Domain-Specific Training: Training models for specific industries (e.g., concrete transport trucks do not have the same characteristics as refrigerated trucks for fruits and vegetables).

In conclusion, by offering an initial increment that improved productivity and taking business feedback into account, we were able to help dozens of experts in just two months. They can now devote more time to advising their clients on high-impact actions rather than spending time searching for the best emission factor to produce a carbon footprint.

While we recognize the importance of properly scoping a project, we are, above all, obsessed with rapid user feedback—the best way to meet client needs.